Anamchara, pronounced: an-m-ha-ra, is Irish Gaelic for “Soul Friend”.

This ancient distinction originated with the druids. Later on it gained notoriety with priests and the ordained after Christianity came to Ireland. While Ecclesiastics (as Christian clergy were often called in the Middle Ages) considered an Anamchara essential for confession, the ideal transcended the mere act. A soul-friend was trusted for life.

It was a common saying, “Anyone without a soul-friend is like a body without a head”.

Some of the best historical examples of an anamchara and his or her purpose, can be found in Irish monasticism.

In his book, Sun Dancing: Life in a Medieval Irish Monastery and How Celtic Spirituality Influenced the World, Geoffrey Moorhouse tells us how the idea of an anamchara shaped the early development of Irish monasticism. Young monks entering the monastery life were meant to learn by imitation. These youths were assigned to a senior member in the monastic community. This mentor would watch the young monk and give spiritual instruction. The senior member was also the one to whom the youth made confession.

Being an anamchara was not an easy task for the elder. Moorhouse elaborates…

It was said that “…soul friendship was a parlous duty for, if one imposes on a man the penance that his sins have deserved, he is more likely to break it than to perform it. If the confessor does not impose the penance on him, that man’s debts fall on him.”

This relationship and its implications was to remain strictly between the monk and the anamchara. Lisa M. Bitel, in Isle of the Saints: Monastic Settlement and Christian Community in Early Ireland, tells us that even the abbot, who served as head of the monastery, was not involved between a monk and his confessor. The relationship was regarded as so private that the anamchara replaced the abbot as the monk’s father figure.

An anamchara, according to Ailbe’s Rule, was to discipline in a fatherly fashion…kindly reproving the monk under his charge when that individual was found to be at fault in some way. If the monk refused to confess his guilt, his anamchara would send him away privately to sulk and consider his sins.

The Ceili De (clients of God) were among the more distinguishable groups of reformed ascetics in Ireland during the 8th and 9th centuries. They considered the bond between a monk and his anamchara so strong that not even physical distance should come between them, even if that meant a monk traveling clear across the country to be with his anamchara at his deathbed.

Of course, at times a monk would find that his chosen anamchara was not a good fit.

Hagiographers (big term for people who write about the lives of Saints), cite examples of specific saints switching their confessors when they grew older or found that their specific needs had changed. Certain monastic houses often garnered a reputation for specializing in one area or the other – be it in medicine, theology, arts and sciences or the production of manuscripts. An aspiring scholar might leave his monastic home and confessor in order to gain further tutelage under a new anamchara who served in such a reputable house.

Young monks were usually educated at home or their local church before formally entering a monastery. However, sometimes another factor would come into play.

Fosterage

The idea of fosterage was very prevalent in medieval Ireland and was rooted back in early Brehon law. Most families, particularly of noble class, sent their children to be reared by foster parents at a young age – ideally seven years. The child would often remain in fosterage (not always with the same foster family) until the age of 14 (if a girl) or 17 (if a boy). Fosterage was promoted in Irish society, primarily to strengthen ties between ruling families and clans. In many instances, the foster parents were close relatives of the child.

Even so, the fosterage between a monk and his anamchara transcended the kind established by the rest of their society. The anamchara provided a relationship free of the burdens that came with a normal fosterage – inheritance, authority or duty. There were no such hindrances to mar the transparency and open communication between anamchara and youth. As a result, their companionship was uniquely affectionate.

You could liken it to a best friend. Someone who understands you on the most intimate levels. No wonder an anamchara was regarded as a “soul friend.”

When I was first introduced to the concept of an anamchara in my research I was struck by both the simplicity and the depth of the relationship. I just had to create a story around this idea of mentor, confidant and friend.

As a Christian, the idea of anamchara is even more profound. You see a form of discipleship being exemplified. The anamchara acts as the physical picture of Christ to the youth. He who is our Savior, and the Lover of our Souls, desires to foster a relationship with us in which we confide in Him wholly with abandon. In His very nature Jesus truly is our “soul friend”.

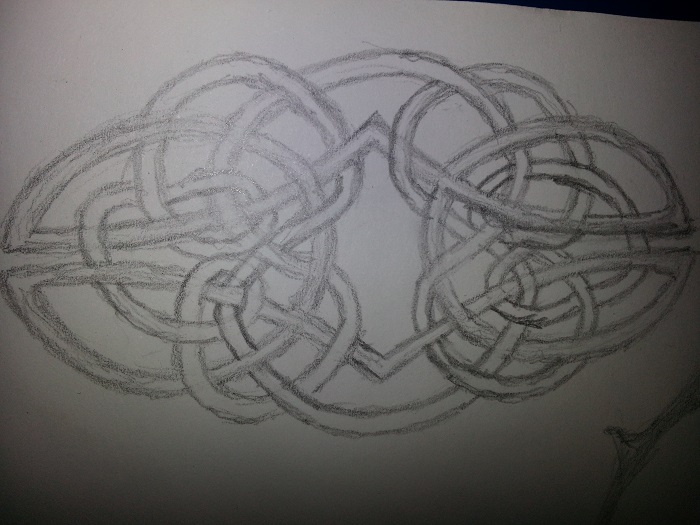

Well as promised, I added a little something more to this post. Creating the featured image for this article was a fun endeavor for me. Through my research of 10th century Ireland, I came to adore Celtic knotwork – which is a true blending of the Irish and Viking styles which developed from that period. This piece was my first attempt at creating Celtic Knotwork, and as I’m sure you can tell, it was all free-hand.

It features the name “Anamchara” front and center. Beneath it is the same word written in Ogham (pronounced “Oh am”), which was the earliest form of writing in ancient Ireland.

As you observe the featured image, you may also note another conspicuous image hiding in the vines.

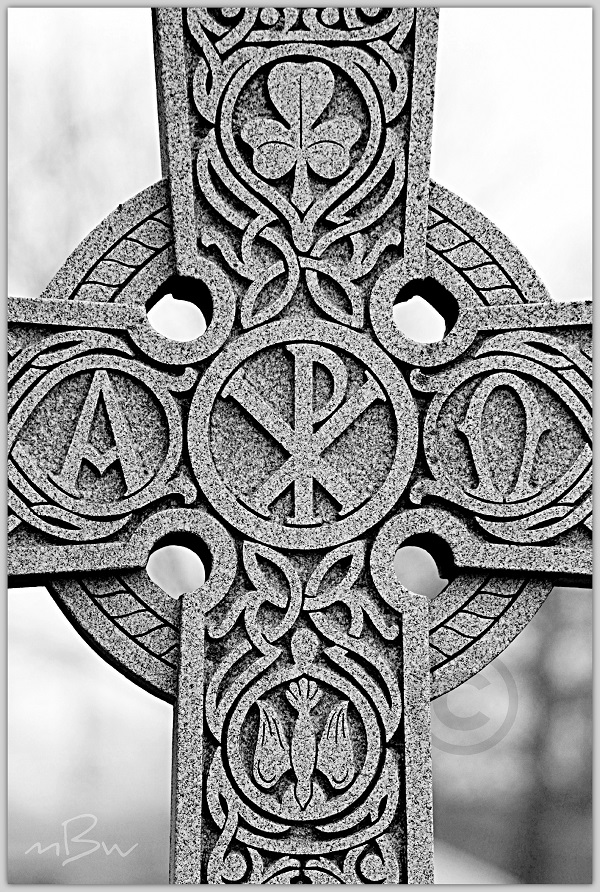

The Greek letters “Chi” and “Rho”, a Christian symbol made famous by Constantine, which represented Christ and the cross. I wanted the anamchara to stem out of the “Chi-Rho” as a symbolic picture of who our true Anamchara is.

The idea of an anamchara is a beautiful picture, and though my artwork is shoddy by comparison to that wonderful imagery, I hope that it conveys in some small portion the awe it strikes in me of the knowledge that we have such a wonderful Councillor, Mentor and…

Soul Friend.

Instructive and beautiful!

Thank you Maria! This is a subject I’ve meant to revisit. Hopefully, I’ll get the chance to address it further in the future.

God bless your labor of love!